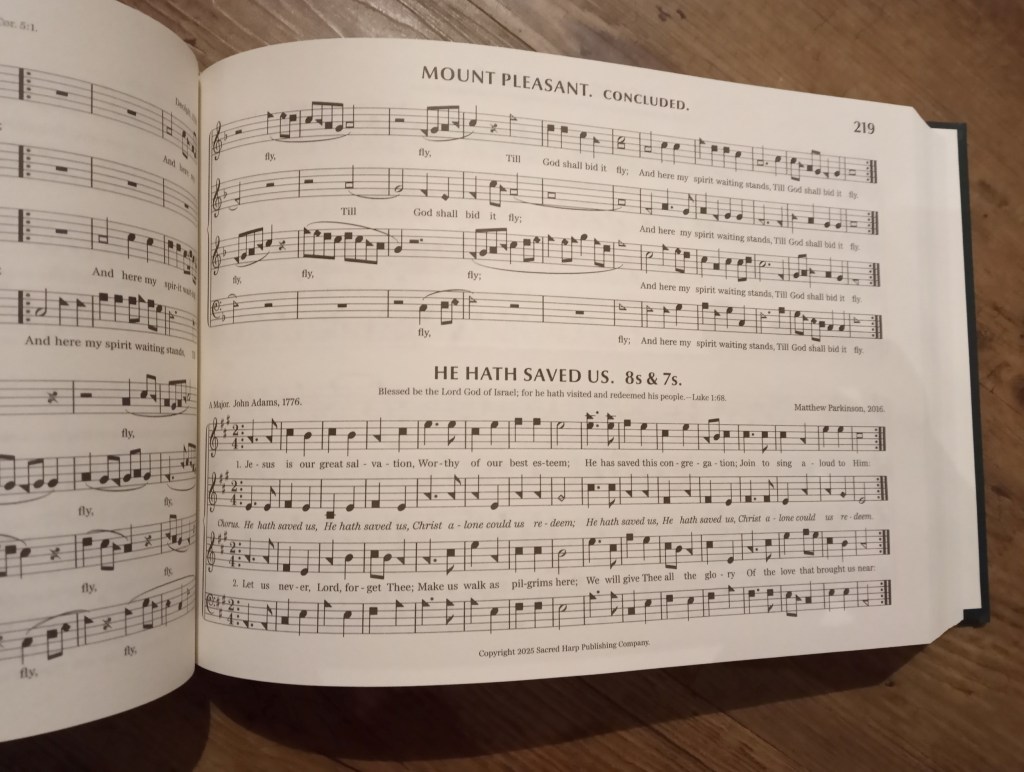

We’re very proud that Matthew Parkinson of Manchester Sacred Harp has two songs in the 2025 revision of The Sacred Harp. The week before the launch of the new book in Atlanta, Harriet Monkhouse and Jo Kay interviewed him about his discovery of Sacred Harp, how he composes songs, and how he feels about his songs becoming part of the canon.

HARRIET: Let’s start with your musical background.

MATTHEW: I’m from a musical family. My dad used to play Irish flute, and my mum can play piano. Classical music was always playing in my home when I was growing up. I did piano lessons as a kid, which I hated, then trumpet lessons, which were a bit better, and then I moved to drum kit and percussion – I played in orchestras, jazz bands and big bands. I was about to do maths and physics at Uni, but decided “No! Music is the thing.” Then I got into choral singing, and the drumming slid off to the side.

I first found Sacred Harp on a forum for ancient Mesopotamian musicology. It was a bunch of really eccentric scholars talking about music in Mesopotamia, and one posted “I’ve just found this documentary called Awake My Soul: the singing’s amazing!” So I went to the website, and it was one of those noughties websites that played music automatically. It played an old archive recording of either “Idumea” or “Windham”, I can’t remember which. It struck me. I got obsessed, listening to the recordings. But I assumed “OK, they do it in the Southern states, but I’m never going to be able to do that.”

I started a PhD in music composition, but I hated it. I just wanted to sing. So I made a list of English cathedrals which took choral scholars [student singers paid to sing in the choir] and gave you accommodation. This was quite late in the year, but Norwich Cathedral said “Oh, someone’s just dropped out.” By September 2011 I was in Norwich. Singing in a cathedral pays a pittance, but with no rent you can have a job in a café and muddle your way through if you don’t have dependents.

Then I saw some flyers from Norwich Sacred Harp in the library, and thought “There’s that Sacred Harp thing!” The group had just been started by Cath Saunt and Fynn Titford-Mock – I owe them a lot.

It was such an exciting time for me. I was singing Choral Evensong six nights a week, and then going to Sacred Harp singings on Saturday, so my voice would be wrecked for the Sunday morning service. My friends would say “Oh, Parky’s been doing that Sacred Pap again.” They called it Sacred Pap to poke fun at me.

I loved singing in the cathedral, but my voice isn’t really suited to classical singing. I do a folky style more easily. It also relies on sight reading. I’m a good sight reader, but I was the worst in the cathedral choir. And the religious pomp, day in, day out, started to get a bit tiring. I thought “I want a change.”

In Norwich I met Leilai, my wife, who was studying there. After she finished her Master’s, we moved to Bristol because we had heard good things about the city. We packed a car with our stuff and drove to the South West. By that point I was fully into the Sacred Harp singing.

Now, I’m in Cheshire, of course. We moved here in 2019 to be closer to family when we were having our second child.

JO: Was the Sacred Harp singing in Bristol part of your calculations in moving?

MATTHEW: Not really, though knowing there was a group was attractive. But the group then wasn’t fully fledged. Michael Walker had given a singing school, but none of the singers had yet been to an all-day singing. They had the first Bristol all-day in 2014, the year we arrived.

HARRIET: So one of your songs in the new book, “Gwehelog”, was composed in 2015, a year after you arrived in Bristol?

MATTHEW: Yes, Gwehelog is a long-running singing in South Wales. In fact, it’s the only all-day singing in Wales. Chris Brown and Judy Whiting were driving down from Yorkshire to run it. It was a labour of love, but they were getting to a stage where they didn’t want to do that. It’s just over the Severn from Bristol, so they asked if the Bristol singers would be interested in taking over. I wrote “Gwehelog” for Chris and Judy, to thank them for entrusting us with their singing.

HARRIET: And then you wrote “He Hath Saved Us” a year or so later.

MATTHEW: I’ve no memory of how I wrote “He Hath Saved Us”! I don’t even know where I got the text. I use the website Hymnary a lot. You can search it by language, author, poetic metre. So if you have a tune and no text, you can search Hymnary for texts to fit the tune.

Like most composers, I nearly always start with the text. The problem in starting with the tune is that you need the right number of notes for the number of syllables in each line. You can write a tune and then struggle to find poetry that fits. So really, it all starts with the poetry, and I feel that the mood and content of the poetry implies music.

JO: Are you looking for text to write a song to, or is it just “I really like these words”? I could understand writing a song – you’d wake up with a tune in your head, and work it up. But why are you looking for text? Are you reading the Bible and finding grace… graceful words?

MATTHEW: Often, if I’m in the mood for writing a song, I flip open a hymn book and leaf through it. They’re mostly words-only hymn books. You might see a hymn, and you just like verse four. You don’t have to use the whole thing.

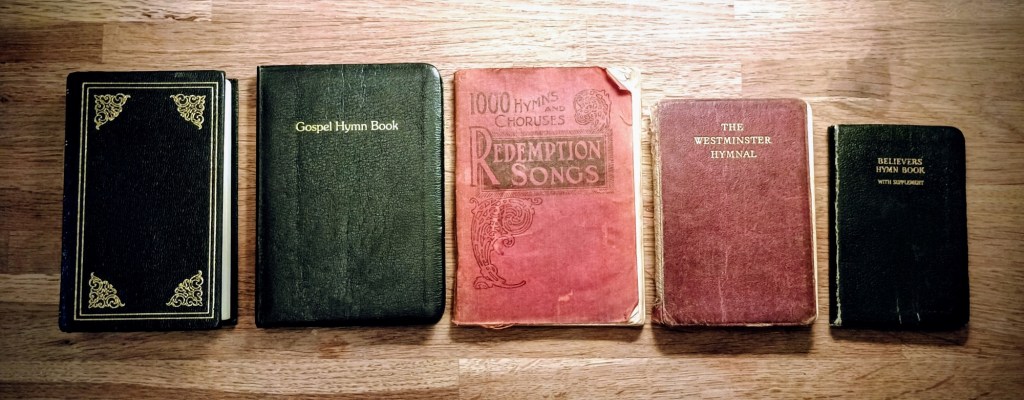

I’ve got a little stack… have you ever seen Primitive Hymns, by Benjamin Lloyd? It’s used in Primitive Baptist Churches. It has a lot of Isaac Watts, and it seems like nearly every shapenote text is in it.

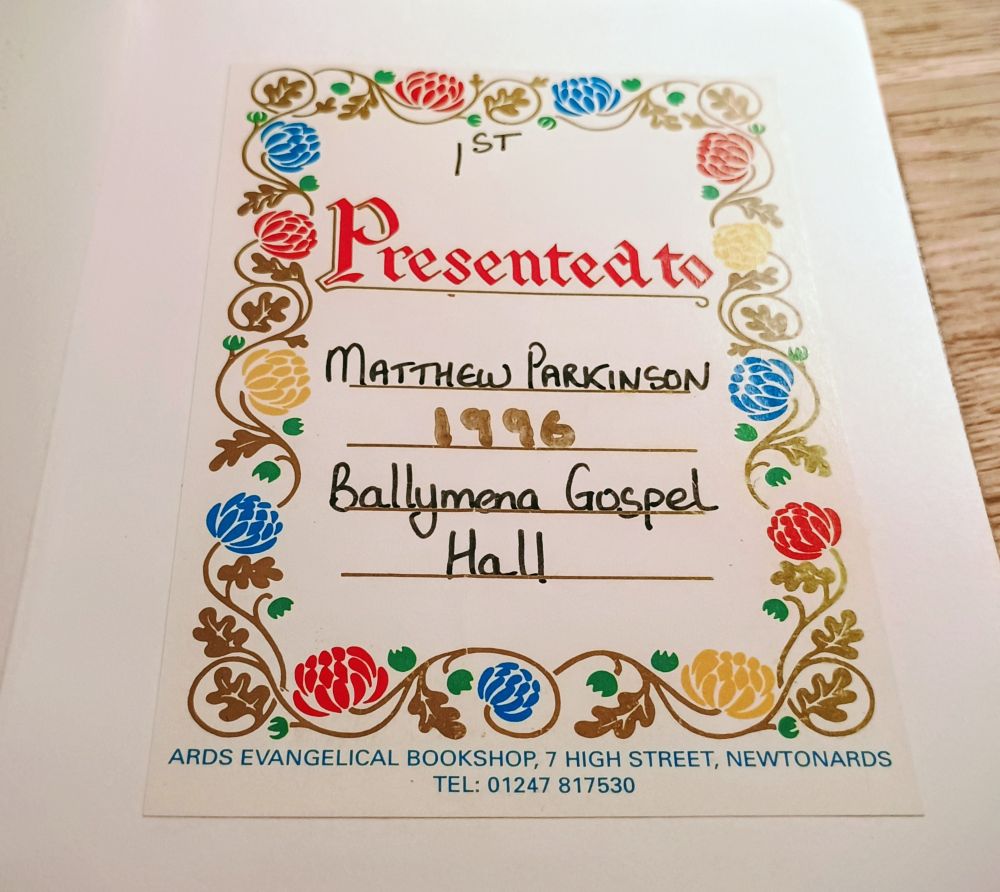

Then I’ve got two from childhood. The Gospel Hymn Book was a Sunday School prize… “presented to Matthew Parkinson, 1996, Ballymena Gospel Hall”. I’d have been nine. They’re mostly evangelical hymns, and it’s used by Gospel Halls in Northern Ireland, the type of church my parents attend, so it’s what I grew up with. And there’s the Believers Hymnbook, given to my dad by his father in 1978. They have slightly different texts to the Primitive Baptist hymnals – the theology is less Calvinist. And I have The Westminster Hymnal, which is Roman Catholic, and another Evangelical one called Redemption Songs.

The text for “Gwehelog” is used in the Cooper book [a parallel Sacred Harp tradition] for the song Hester 336t, “I love to see the Lord below”. I thought it was a lovely text to write another tune to. The one in Cooper is in four, quite a different tune, so we’ve now got alternative tunes for the same text. And the fourth verse of my version, “He shines and I am all delight”, isn’t in Cooper – it’ll be unique to the 2025 revision.

JO: Have you ever written original text?

MATTHEW: Not my thing. I got AI to do it once!

JO: How very Laurie Anderson!

MATTHEW: It was OK, but a bit weird. Not many people write their own text. I think it’s harder if you’re not a believer.

JO: Are secular words ever used?

MATTHEW: The Social Harp has secular songs – about Napoleon Bonaparte, and sailors, and that kind of stuff. I’ve only used secular text in one song, which is named after my daughter, Annabel.

HARRIET: Have you composed songs that weren’t in the Sacred Harp style? Or music that was completely different?

MATTHEW: Yeah, in my degree, I majored in composition. I wouldn’t call them songs, though. It was avant-garde classical music. Wanky stuff. It was interesting, intellectually, but I didn’t want to listen to it, and I didn’t care if anyone performed it. It’s quite strange, then, when your first shapenote song is just this simple little piece, and you’re really, really excited for people to sing it.

HARRIET: So these two songs – were they composed as Sacred Harp tunes?

MATTHEW: When I’m writing in four shapes, I don’t really think of it as Sacred Harp, I just think of it as shapenote music. I also write songs in seven shapes, and they’d be in more of a Christian Harmony style. It’s interesting how our songbooks and music notation have come to define the genre.

HARRIET: So what are you trying to achieve with the different parts? Harmony? Everyone having a good part to sing? A particular mood?

MATTHEW: All of it! It has to be fun to sing. The harmonies have to be good, the melody catchy, and the poetry and music have to marry. I think best songs have all of those things working together.

Every song has a unique character or personality. In “Gwehelog”, for example, I wanted the harmonies to sound rich, yet bright at the same time. And the mood to be upbeat, but with a reflectiveness about it. I hope I achieved that. “He Hath Saved Us” is different – an upbeat chorus that should get firmly stuck in your head after one hearing.

HARRIET: Which order do you compose the parts in?

MATTHEW: The classic order in shapenote composition is tenor, bass, treble, alto. So the tune first, then the bass, which is the foundation of the house, then the treble, which is like another tune, and then the alto, to fill in the gaps. That makes it sound like the altos are bottom of the pile, but they really aren’t! The altos are like a Leatherman multi-tool. The basses tend to have one function – provide a foundation for everything else. Whereas the altos can fill harmonic gaps, add intensity in their upper range, drive the rhythm, and create a lot of smiles when they have a solo. The quality of the alto part can make or break a song. In fact, one of my most prominent memories of the first convention I attended, Cork 2013, is the sound of the alto section. It was so intense and bright and searing, like something on a hot pan. Amazing.

HARRIET: How do you get the parts to fit together? I’m told this is called horizontal versus vertical composition – are you driven by the tune going across the page, or the harmonies going up and down the staves?

MATTHEW: It has to be both. At the beginning, it’s all about the tune. You’re writing that tenor line, and trying to get the tune just right. Then the bass defines where the harmony’s going to go. Well, that’s how I feel it, but I sing bass, so that’s a very physical experience for me. Once you start to write that, you’re thinking “This might sound good, but it’s going to clash with the note on the tenor part.” The further you go, the more your options narrow. Writing the bass, you’ve still got a lot of freedom. But once you’ve got the tenor and the bass, the notes you can use for the treble are restricted. I find the treble hardest to write. The alto’s even more restricted, but weirdly I find it easier. There’s almost a freedom in being so limited. And because Leilai sings alto, I’m familiar with how alto lines work. She sings them around the house. Treble lines feel totally foreign to me. Sometimes I sing through a treble part and think “what on earth are they doing?”

HARRIET: So how do you work out if it will sound good? Do you and Leilai sing it, or can you hear it in your head?

MATTHEW: Lots of ways! Every composer is different, and we have to find our own methods. I can hear a tenor and a bass in my head. Once I get to three parts, I can hear maybe 50% in my head. At four it becomes difficult. One technique is to think of the scale as seven notes: fa sol la fa sol la mi… 1 2 3 4 5 6 7. Then if you work through the parts and number all the notes, whenever there are two consecutive numbers in a vertical chord, like a 2 and a 3, at the same time, that’s a clash. And generally you have to change one of those notes. 1 and 3 would be fine, or 2 and 5, but not 2 and 3, not 3 and 4… That technique won’t necessarily result in great harmony, but it tells you where the clashes are.

I also put it into music notation software and use the playback function to test harmonies. The midi instruments sound terrible, but I’ve found brass instruments like trumpets and trombones have a strident quality that mimics the sound of shapenote singing well enough for me. Sometimes, when you hear the playback, one chord to the next can really work, and then in another it feels like the momentum disappears, or the texture suddenly changes. I try to hear when there’s something jarring, clunky, or awkward. At that point I think “I like it, but that chord there, something’s not right.” Maybe I’ll swap the treble note with the alto, or something like that, to see if that makes it better. I fiddle around until it sounds the way I want.

I sometimes do a multi-track recording, and listen to that, but generally I find it too much effort.

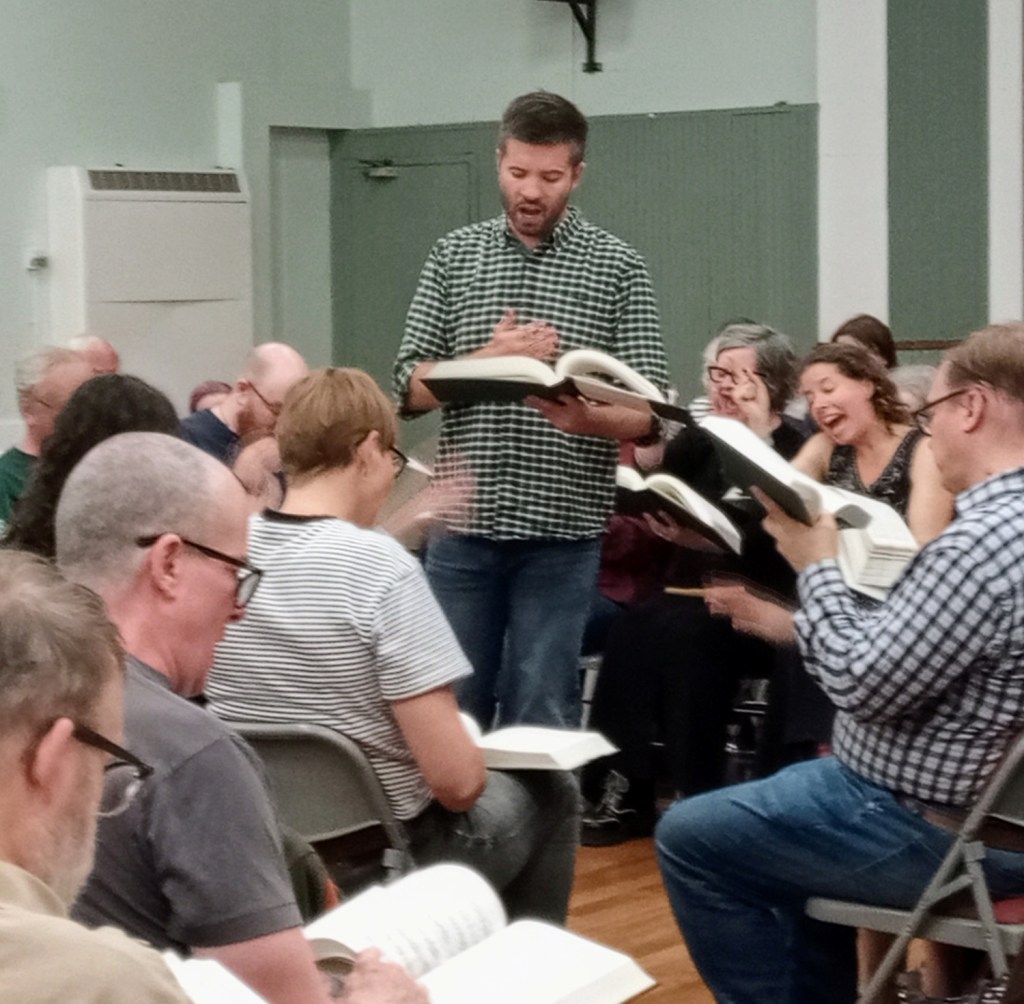

The ultimate way to test your song is to hear a class singing it!

JO: Once, on YouTube, I found you doing four different voice parts… actually, Miss Piggy was doing alto.

MATTHEW: [covers his face] I set up that YouTube account on a now deleted email address, so I’m for ever locked out. Some of those recordings I’d probably remove now, they’re a bit embarrassing. But Miss Piggy is there for eternity and I can’t do anything about it. It’s the Christian Harmony song “Youthful Blessings” [included in the 2025 revision of the Sacred Harp as 544].

JO: Do you feel tempted to stick little jokes or private references in?

MATTHEW: I’m tempted! I’m not sure I’ve ever done it. I’ve played around with silly things, but the serious and the silly stay separate. Leilai and I once tried to do a seven-shape version of the Wombles theme, but we never finished it.

One silly thing I do… I sing tunes I hear, like random tunes on the radio, in shapes. It’s a bit like trying to do a cryptic crossword, at first it feels impossible. I hear Eminem, and think “How do I put that into shapes?” Then something clicks and you can do it. You start to hear the world around you differently. A lot of doorbells are “sol mi!” Actually, that was in seven shapes. I should probably stick to four for this conversation!

JO: Are your songs going to be sung by the robot on Sacred Harp Bremen’s website?

MATTHEW: We’d need to ask Harald!

JO: I hope so, how else are we going to learn them?

[November update: Harald has done it! Sacred Harp Bremen now provides scores and robot singings of all songs in the 2025 edition, including Gwehelog and He Hath Saved Us.]

MATTHEW: You know, there’s this great system called shape notes…

HARRIET: Yeah… but some of us still can’t…

MATTHEW: They’re quite easy songs. Because I proof-read the new book, I saw pretty much all of the new songs, and there’s plenty of trickier fuging songs to get stuck into. Mine are on the simpler end, just half a page each.

HARRIET: Do you have a style we’ll recognise in both songs?

MATTHEW: Oddly, I submitted seven songs in a selection of keys and time signatures, but the two selected are both in A major, and in both I wrote a high fa for the trebles, higher than usual for an A major song. So I feel people will look at those and think “Oh, he’s that guy who writes the high fa in A major songs.” But those are the only two I’ve ever done that in, and they were the winners. Strange.

HARRIET: Have you been influenced by other Sacred Harp composers, or features you like in particular songs?

MATTHEW: Probably less composers, and more an era and style of song, though I do like B. F. White, E. J. King and J. P. Rees. William Walker is great too. I prefer the Southern style from the mid to late 19th century, and more recent songs written in that style. Those older songs by 18th-century writers don’t appeal to me so much. Like Daniel Read – he’s not my cup of tea. I like some of them, but I don’t write that way.

HARRIET: How will you enjoy leading your songs, or would you prefer to see other people leading them?

MATTHEW: I don’t think I’m going to lead them! I will if someone wants me to, or asks me to help them. It’ll be interesting to see how composers interact with their own songs. I think Leilai wants to lead “He Hath Saved Us” at the UK convention, so I’ll let her take that one. I’d rather lead a song from another composer who’s a friend of mine.

HARRIET: You don’t have any worries about people doing them all wrong?

MATTHEW: No. In Atlanta, they’re singing all the songs by living composers in one day. They’ve asked the composers if there’s anyone in particular they’d like to lead their songs. I’ve asked Thom Fahrbach to lead “Gwehelog”, and Sam Cole and Vicki Elliott to do “He hath saved us” as a duo. They keep asking questions like “What kind of tempo did you hear this in?” or “Do you hear this song having no loss of time?” They obviously want to do the song as I imagined it. But I think the fun thing is, if people are going to lead the songs they’ll do them the way they want to.

JO: How do you feel about that? What if someone does it extremely slowly or really pacy?

MATTHEW: It’ll be fine. Initially you’ve got this sense of ownership. But when it’s in the book, you’re giving it to the community. You don’t have any right to say, “I want it sung this way and only this way.” That’s not how it works. If someone wants to lead it slowly, they can lead it slowly.

We’ve never had singings in our community where multiple people you know are in the book. Sometimes you roll your eyes at a song – you’re going to have to be more careful now! It’s a different dynamic when the creators are in the room.

JO: I’m interested in the idea of legacy – how we treat the songs, and the writers. We have a historic view of the composers, and that’s going to shift. But thirty years on, we’ll say “Oh, I knew Matthew, I used to sing with him,” and then someone will say “I once met him at a buffet, he was lovely.”

MATTHEW: And then it’ll be “I knew somebody who knew…” In the grand scheme of things, even legacy disappears fairly quickly.

JO: The songs will go on to have a life of their own?

MATTHEW: A friend pointed out to me recently that some churches still have copies of the Sacred Harp to use in their services. But so many songs in this revision have been written by non-believers. It’s an interesting idea for believers to be singing these hymns. This has always happened. Hymns in the Church of England – many of the organists weren’t believers, but they were writing music for the church. Christianity was a central part of my upbringing, yet I was never a believer, and now I’m writing hymns that are going in a hymn book… there’s something a bit odd about all of that. And I’m sure believers might find it odd, too.

But really, I’m just happy this is happening, that people want to sing the songs. It’s really exciting. When I was in Bristol, and started writing shapenote music, there was a little group of us – me, Steve Brett, Barry Parsons, Bridget McVennon-Morgan, Rachel Wemyss, Samuel Turner. Often someone’d bring a song and we’d sing it, all bouncing off each other. And now Samuel, Barry and Steve have songs in the book, and other friends from the UK, too. I’m so happy my friends have got songs in!

Leave a comment